It always amazes me how we limit growth by not investing fully in innovation. While most large companies want to become more agile and innovative, many of them fail to turn this wish into a reality.

It always amazes me how we limit growth by not investing fully in innovation. While most large companies want to become more agile and innovative, many of them fail to turn this wish into a reality.

There is this consistent need or pressure to grow, yet that specific needle stays stubbornly stuck in low growth numbers, even with all this innovation talk and desire. Why is that? We know you simply grow a business by choosing a mix of investing in innovation, merger, and acquisitions or releasing your resources into more profitable activities. Innovation as a dedicated activity still sits uncomfortably within many organizations.

To try and catalyze growth, companies undergo perennial reorganizations, often to revitalize themselves. According to a Deloitte report, 50 percent of companies are undergoing an organizational transformation, yet only 11 percent think they will succeed. What’s worse, 70 percent of transformation programs do fail. In these failures, we only seem to continue to layer on complexity as a further stop-gap measure.

It is no wonder we’re growing increasingly pessimistic about making a positive change to a different transforming model within organizations. Without innovation taking a more leading transforming role, most of our established companies will continue to struggle to break out of their existing approach to business. Far too many are mired in a past business mindset.

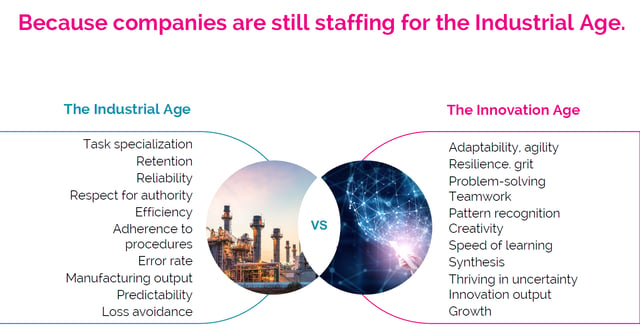

One basic argument is that no matter what we do to undertake change, we seem stuck in the Industrial Age of the last century. We claim we are in the innovation age, one where a digital transformation will finally transform us, yet it remains elusive. I recently came across the below illustration of the struggles we seem to be having, in changing our companies from the industrial age to the innovation age. It depicts much of the constraints around how people are still working.

Source: www.swarmvision.com

What is holding this innovation age back?

To start, we face strong countervailing forces that restrict our abilities to break out of our past to move towards a new way of working. Pursuing old business paradigms of how a company should be run is not helping us.

Is it because of this traditional way of working, designed into the company, that we are all becoming disengaged and disenchanted with what we do? We’re often left feeling powerless to influence the type of change that we want to see, to release our creative juices and not simply to make those quarterly reporting numbers or get caught up in constant cutbacks when they don’t meet market expectations.

We are increasingly facing very different competitive pressures. This is a very “VUCA world” – the volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity of general conditions and situations we operate within. Pressures are not just external. We often bring them upon ourselves, as we were not anticipating, investing, and looking to build a different type of business. We fail to invest in foresight and insight, continually not adapting and adjusting our organizational skill set around a more agile, adaptive, highly responsive innovating and creative organization.

Every time we begin to call on innovation, we face negative forces. These are the ways we still wish to judge business – on its short-term results and its ability to limit risks. To give returns to shareholders that safeguard their investments. To achieve this, we look for maximizing efficiency and focus on the continued extraction of value from our core. We talk about investing in the future, in making adjacency moves, and in encouraging risk – but is that really the case?

For many, risk management has never been seen beyond the protection of the status quo. This attitude toward a risk-containment approach restricts innovation. It is actually limiting or even sacrificing the future by not investing in all the aspects of growth, especially bold explorations of new growth avenues. They fail to invest in a clear, distinctive capability of innovation capacities, that is fully integrated within their organization. Innovation stays outside the current core.

I am not proposing we abandon the need to protect our investments and to provide a reasonable return for investors. Instead, I’m suggesting more of a conscious shift where we focus on building more effectiveness, extracting more synergies, and exploring greater growth options.

Can you imagine having the same number of people involved in innovation growth as we have that manage the finances of a business? In most companies, we have small, dedicated innovation teams of five to 10 people trying to take on this Herculean task of growing a business through innovation. They are reliant on engaging others, focusing on their specialized areas to hand over their time to innovation. This is often above and beyond their daily job responsibilities.

Approaching innovation in this highly constrained way is simply not a recipe for success even though in recent years we have been trying to make the subject of innovation more attractive by tempting people to join in and participate in multiple ways.

Extracting innovation has become very complex

Let’s all agree that we live in a complicated world. We are continually witnessing growing threats all around us. Competitors are disrupting – even ones who were not around 12 to 24 months before. We see mergers, closures, or once great beacons of industry shrink before our eyes due to new alternatives. I have in mind here GE and the dramatic restructuring pain it is currently going through. We feel increasingly unsafe unless we happen to be one of those sitting in a technology-related business where growth has been extraordinary in recent years (e.g., Apple, Alibaba, Amazon).

But first, when you think of innovation, what comes to mind?

Source: European Commission

In “Opportunity Now: Europe’s Mission to Innovate,” a 2016 European Commission report (a mere 360 pages long), the author makes this point:

“Innovation is also more complex than ever. Complexity, chaos, and non-linearity have been seen since the 1970s as the defining features of our age. But still, our advanced societies find it hard to make robust policy for a complex innovation system.”

We should always start by recognizing innovation as a complex system. As the report defines, a complex system is a place where:

- no one can have a complete map of the actors and forces at play,

- the system’s behavior is not simply the sum of the behavior of those parts,

- feedback loops surprise us and change the behavior of the system,

- the system is “autopoietic”: behaving in a self-driven way and not just in ways we have yet to understand.

The report also questions, quite rightly, that having a pipeline theory as too simple. The author suggests innovation is not like a Roman aqueduct, designed to allow water to flow; instead, it’s a “muddy pond,” rich but obscure.

That is not a comfortable view for business leaders determined to limit risk, maximize resources and be consistent to extract efficiency and be fully effective. Innovation flies in the direct opposite to this need of corporate design. So, we have become highly creative for innovation to be allowed to operate under the same roof as these efficiency and extraction rules and regimes.

We have come up with multiple ways to exploit innovation. It can contribute to the business model, explore the margins, undertake core renovation work, experiment, and prototype, and be completely new to the world. But it always seems to be divided up in different parts of the business. I often feel innovation activities within companies are a continuing set of experiments, needed but not systemized, fragmented in its potential energy by this underlying need to keep it under control and to minimize risk and feel exposure.

Are we dissipating innovation resources or recognizing that one-size does not fit all?

We are fragmenting much within innovation. Is this good or bad for the longer-term? “The Ten Types of Corporate Innovation Programs,” an article was written by Jeremiah Owyang, founder of Catalyst Companies, provides a terrific list of possible types of innovative programs to consider. But by adopting too many, you fragment and possibly dissipate your innovation resources. Owyang offers a good description and examples that make this a highly useful reference point. Which do you undertake or are actively considering?

Many others are emerging beyond these ten types, where “open” sets the tone for building creative spaces, in lab designs or investment by different avenues of VC funding, internally and externally.

To begin with, these ten types of corporate innovation programs form a good starting point to consider what works for you. Which strategies can push innovation further down or out of the company and help move the growth needle for your innovation program? Check out Owyang’s description below.

The Ten Types of Strategy for Corporate Innovation Programs

1. Dedicated Innovation Team

Corporations often start with staffing an innovation team within the company of full-time employees dedicated to developing the strategy, managing, and activating innovation programs. These leaders are experts at internal communications and are change agents.

Example: MasterCard, Hallmark, and BMW all have innovation teams dedicated to new business ideas, as does Nokia. Learn how Nokia’s innovation team works here.

2. Innovation Center of Excellence

Innovation can’t happen in a single group; without broader institutional digestion, new ideas will falter and fall. Some corporations are setting up cross-functional, multi-disciplinary groups to share knowledge throughout the company.

Example: Various retailers and consumer packaged goods companies enable this. Read: Creating the Physical Space for Innovation

3. Intrapreneur Program

Rather than rely solely on external programs, internal employees – dubbed “intrapreneurs” – are given a platform and resources to innovate. These programs invest in employees’ ideas and passions to unlock everything from customer experience improvements to product enhancements and full-blown internal startups that are then launched from within the company.

Example: Adobe’s Kickbox program is widely recognized as the leading program. Read: Exploring the Intrapreneurial Way in Large Organizations

4. Open Innovation: Hosted Accelerator or Corporate Incubator

Hosted inside a corporate office, large corporations invite startups to embed at their physical locations and provide them with funding, corporate support, and other perks. This brings innovative startups inside a large company for everything from overnight hackathons to long-term programs. Other variations include online open-innovation programs that request – and often reward –ideas from the crowd.

Example: Allianz Digital Labs in Munich hosts startups, and GE Garages enables startups to partner.

5. Innovation Tours

Frequently inspiration comes from outside, not within. Corporate leaders tour innovative organizations, companies, and regions to discover trends in various industries, learn from speakers, meet partners, and be inspired as they immerse themselves in innovation culture.

Example: European-based WDHB and Nexxworks tour executives in Silicon Valley and beyond. See an example of an innovation lab tour from the University of California San Diego here.

6. Innovation Outpost

A dedicated physical office, such as in Silicon Valley or wherever innovation happens in their market, staffed with corporate innovation professionals whose job is to sense what’s occurring in a market, connect with local startups, and integrate programs back into the corporate HQ. Some of them host partners, events, and startups, thereby spreading the function to Internal Accelerator programs. An Innovation Outpost is typically managed by employees – unlike an External Accelerator, which is run by a third party.

Example: Swisscom, Vodafone, and Nestle have opened Silicon Valley outposts. Read Evangelos Simoudis’ blog for insights.

7. External Accelerator

Corporations partner with third-party accelerators to provide sponsorship and/or funding in exchange for relationships with startups and integration opportunities. Corporate innovation professionals often embed themselves in Accelerator offices, fostering relationships with local startups. These External Accelerators are run by third parties – unlike Innovation Outposts, which are managed by employees.

Example: Plug and Play, Singularity University, Rocketspace, Runway, 500 Startups, Betaworks, and more.

8. Technology Education, University Partnership

Corporations can tap into new graduates, early-stage projects and companies, and the network of an established educational institution. In addition to traditional universities, there are new private versions opening up that are dedicated solely to technology training, like Galvanize and General Assembly.

Example: General Assembly, Galvanize, and most tech- or business-focused universities.

9. Investment

Many corporations place bets among the startup ecosystem, with both small amounts for early-stage startups and larger amounts of corporate funding that yields market data, creates opportunities for follow-on investments, and blocks competitors.

Example: Intel Capital is a leader in direct corporate investments.

10. Acquisition

Rather than build innovation from the inside, many corporations acquire successful startups and then integrate. While often expensive, the startup is often already successful, and the acquisition can help the startup scale further.

Example: As one example, Dollar Shave Club was purchased by Unilever for a reported $1B.

Source: Jeremiah Owyang. Some additional links also applied where relevant.

Are we fragmenting our innovation activities or applying a solution to a specific problem?

We do have to guard against “simply” adopting one type of innovation over another. It needs a deeper understanding of what we want to achieve, and then we seek out the tools, methodologies, and solutions. Diving in and experimenting has some value, but some clarity in what you want to build in innovation capacity makes sense first.

If we apply one approach, we are in danger of “shoehorning” innovation to fit a program. Maybe we are then not allowing the idea or innovation we had in mind to evolve in its own way – in its natural path. Perhaps we are only responding to a top-down pressure of fitting initiatives into that same pattern of seeking efficiencies that fit within an organizational design that will eventually choke innovation.

We need a new call for change based on a focused innovation mindset

For the majority today, we are at this countervailing point where innovation is in need of breaking the impasse. We need a different, more holistic set of solutions to manage innovation.

What I want to look at in a series of articles in the coming months is how we can manage risk from innovation differently. How can we build and accelerate different corporate innovation programs? How can we begin to re-equip our talent to build their capabilities and capacities and to recognize that we can design innovation differently to engage in innovation in more transparent, more structured, and more open ways? How can we design our programs more purposefully?

There is a call for finding more methods and approaches that are open and scale well. We need to reset the baseline of innovation through knowledge, collaborations, and building capabilities. We need to build networks and systems designed for this explicit innovation purpose. Let us finally separate “extraction” from “exploration” in the design of companies. We need to strip away complexity within the way we practice innovation today and connect “it” all up in a new innovative design.

***This post was originally provided for Hype and has been republished here

Your tenth example, Acquisition, carries a risk, though. That risk is that the acquiring company merely buys the innovative company to trawl it for assets, ideas and ROI, and doesn’t incorporate the innovation into its own activities or use it as an example to springboard innovative thinking elsewhere in the corporation. After a few years, the innovative ideas are trawled out, the innovative product has been offshored and the target company is just another cookie-cutter subsidiary, to be traded away or closed down, with any ongoing viable products transferred to other divisions through the acquisition of the necessary licences to manufacture/produce and their transfer to the parent.